Amy Bradford traces the history of espadrilles...

You might not expect such a humble shoe to have an unusual story to tell, but it does one that involves art, war and revolution, no less. It begins in 14th-century Spain, where espadrilles - or espardenyas, to give them their ancient Catalan name - were not a fashion item but workwear, worn by soldiers, peasants and anyone who required cheap, practical shoes.

The words espadrille and espardenyas both derive from esparto, the Mediterranean grass traditionally used to make their braided soles. Each part of the shoe was made by a different artisan, with some crafting the flax uppers (now more commonly cotton canvas), others weaving and pressing the rope soles on specially designed benches (known as banca alpargatero'), others assembling the shoe with decorative stitches, and yet more sealing the soles with pitch (replaced by rubber in modern versions).

Over time, different Spanish regions developed their own unique style of espadrille, some with ribbons woven across the front, others with pompoms and contrasting trims. They were worn by both men and women, but managed to transcend their workaday image thanks to Catalonia's national dance, the Sardana. It was performed in a circle, with dancers sporting red caps, wide skirts and espadrilles with ribbon ties that wound around the legs.

For centuries, espadrilles remained a resolutely Spanish affair, associated with the folk cultures of Catalonia and the Basque region in the north of the country. But two things conspired to bring them to wider attention during the 19th century. The first was growing international trade, which saw an espadrille industry spring up in France (the city of Maulon in the Pyrenees developed a particular passion for them) and exports to South America, where the hot climate guaranteed their success. The second, more important factor was the rising tide of nationalism, which affected all of Europe and prompted fierce struggles for independence on the part of ethnic groups like the Basques and Catalans. Rebel fighters from these groups habitually wore espadrilles, which unlikely as it may seem today were a military staple. They were cheaper than leather army boots, easy to replace, and forgiving on baking hot terrain. So it was that they became a symbol of the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), with Catalan rebels marching against General Franco's armies wearing espadrilles on their feet.

Espadrilles weren't the exclusive property of the rebels, however. One traditional maker, Castaer, was requisitioned by Franco's government because of its usefulness to the war effort, which made it clear that the shoes had wider significance. It was an influence that would last into the post-war years, a time when espadrilles acquired cult fashion status. Artist Salvador Dal played up his Catalan heritage and his eccentric persona by wearing lace-up versions with red socks and a skull cap. He was swiftly followed by Hollywood movie goddesses: Rita Hayworth in The Lady from Shanghai (1947) and Lauren Bacall in Key Largo (1948). The latter's outfit of white shirt, dirndl skirt and espadrilles has never gone out of style.

It was Yves Saint Laurent who led the espadrille's next evolution. By the 1970s, the shoe was ubiquitous and the French couturier wanted to move it on a little. An encounter with Castaer's designs at a trade fair impressed him, so he asked the company to make him an espadrille in a new shape: with a wedge heel. Needless to say, the style caught on.

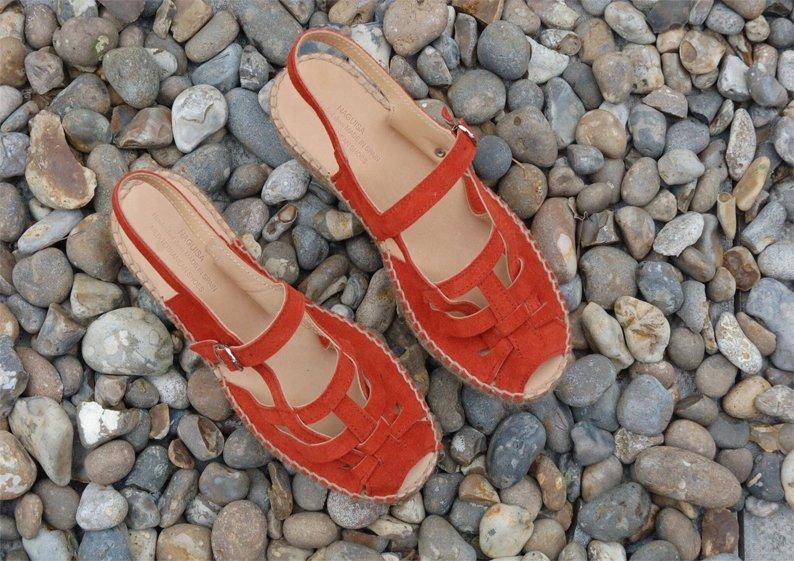

Today, the wedge espadrille is still going strong but few traditional Spanish makers survive among those that do are Castaer and Naguisa, which is based in Barcelona and makes its shoes by hand using authentic methods (it even makes espadrilles for TOAST). The majority of the world's espadrilles are now mass-produced in Bangladesh, but they can't compete with the meticulously crafted originals. Providing you don't venture onto the battlefield, these should last for many summers.

Words by Amy Bradford

Add a comment